Deep Sky Observation - Welcome to Galaxy Season

Part 1: Ursa Major and Canes Venatici

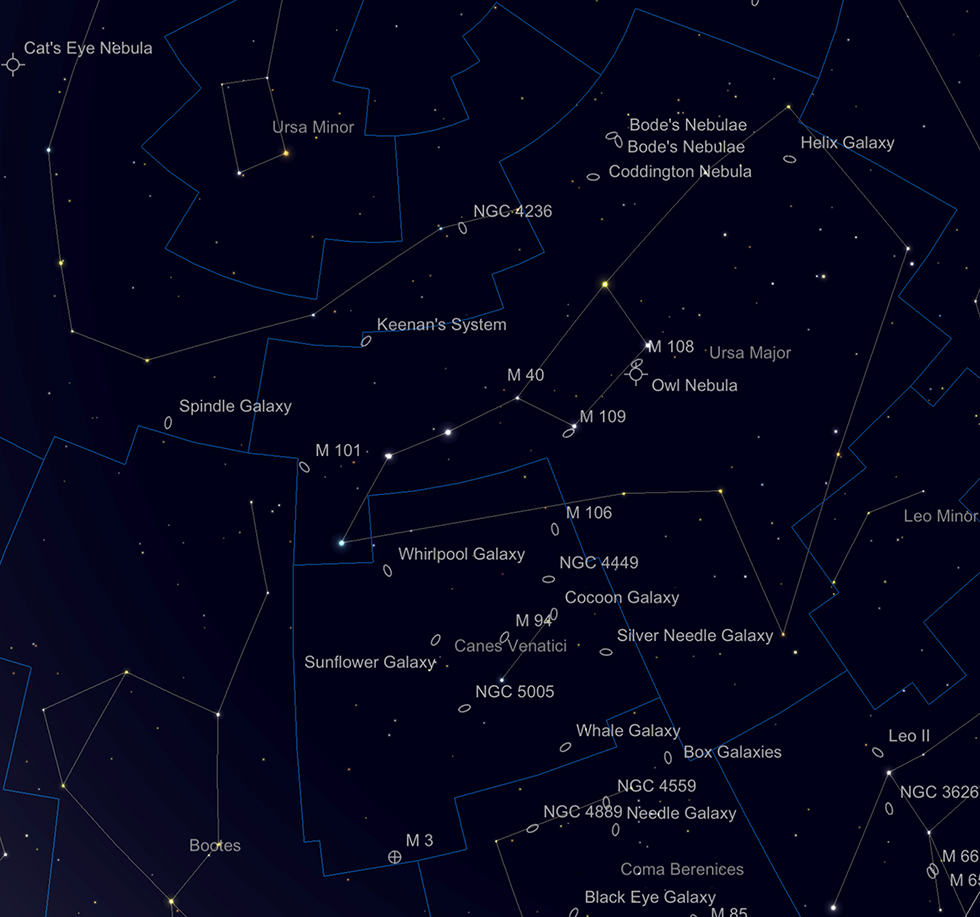

Springtime is traditionally seen as Galaxy Season, so for the next three months, we'll be concentrating on the rich area of the heavens that runs from Ursa Major and Canes Venatici in the North, through Coma Berenices, on into the Zodiacal constellations of Leo and Virgo. This area of sky is well removed from the sweep of our Milky Way's axis and is a major "window" from our perspective out into extra-galactic space. The arc we will be covering, from M81 and M82 in the North of Ursa Major to M104, the Sombrero Galaxy in the South of Virgo takes in 90 degrees of sky and is full of easily-found and observed galaxies.

We start in the far Northern part of this arc (with suitable apologies to readers in the Southern Hemisphere), in the large and imposing constellation of Ursa Major, the Great Bear.

Known the world over for the distinctive question mark-shaped asterism of the Plough or the Big Dipper, Ursa Major actually extends over a much larger area. As such, it is actually the third largest constellation of all, after Hydra and Virgo.

Ursa Major is rich with deep sky objects, the first of which we shall cover is one of the fainter members of this group, NGC2685, the Helix Galaxy. At +11.30 mag and 4.6 x2.5 arc minutes across, the Helix Galaxy is hardly bright or indeed large, but still worth searching out. It can be found in the extreme west of Ursa Major, some 3 3/4 degrees SE of Muscida, Omicron Ursae Majoris - the star that marks the Great Bear's nose. NGC2685 is what's known as a Polar Ring Galaxy, a curious formation caused by the collision and/or interaction between two large galaxies. This causes great loops and rings of stars to form around the exterior of a central galaxy complex. These filament-like structures of gas and star material are often extremely attractive and NGC2685 is a prime example of this. This galaxy is also of the Seifert type, meaning it is energetically emitting radiation, probably as a result of the collision which formed its outer Helix-like structure. It is only in very large telescopes that it is possible to see the delicate ring structures, but they appear as very evident in long duration astrophotographs. The Helix is thought to lie around 42 million light years from Earth.

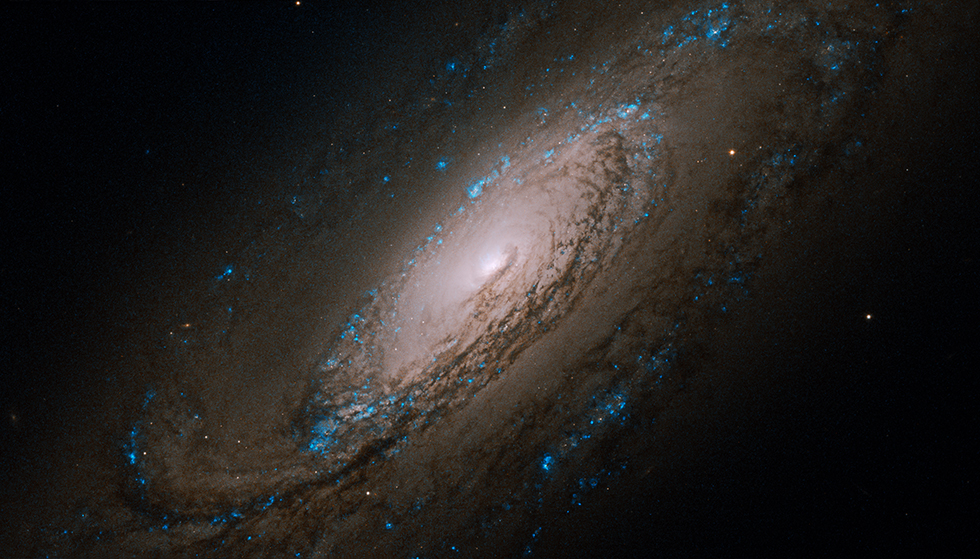

12 degrees or so to the NE of the Helix lie two of the most celebrated objects in the sky and one of the great astronomical "odd couples" (another of which later): M81 and M82. These two galaxies are separated by just over half a degree, but are quite different-looking objects. Of the two, M81 is the dominant - a marvellous sweeping spiral, almost perfectly presented to our perspective, with two major arms, surrounding a large, bright core. At +6.90 mag and 24.9 x 11.5 arc minutes dimensions, M81 can easily be seen in telescopes and binoculars of all sizes - some keen eyed observers have even reported being able to see it with the naked eye under perfect conditions. If this is the case, at 12 million light years distance, it must be the most distant object visible to humans unaided. The M81 group of galaxies are thought to be the nearest collection of galaxies to our own local group. Indeed, some sources suggest that we should actually see our local group of galaxies and the M81 group as a larger collective, as there is some evidence of gravitational interaction between the two.

M81 was discovered by Johann Bode in 1774, along with neighbouring M82. As such both objects are often rather confusingly known as Bode's Nebula. Pierre Mechain independently discovered it in 1779 and Messier added both M81 and M82 to his catalogue two years later. In a telescope of 8-inch aperture and above, the true Spiral nature of M81 really begins to reveal itself - indeed it is one of the few spirals that show real evidence of its shape at such apertures. In long duration images, M81 practically leaps out of the darkness and given it and M82's proximity to one another, it is hardly surprising that these two objects are amongst the most photographed in the entire sky.

M82 by contrast is a very unusual object - otherwise known as the Cigar Galaxy (for very obvious reasons). This galaxy is somewhat fainter than its neighbour at +8.39 mag, but is also considerably smaller in area at 11.2 x 4.3 arc minutes dimensions. Subsequently, the surface brightness of M82 is not dissimilar to M81's. M82 is thought to have been somewhat deformed from a regular spiral structure by interaction with M81 and is bisected by a deep red lane of heavy star forming material. This bisection is clearly visible in telescopes and spectacularly revealed in even modest length exposures . This region looks almost organic in images, with feathery, root like structures shooting in both directions perpendicular to the galaxy's major axis. The power behind this structure seems to be Supernovae, which have been thought to have occurred in M82 with almost metronomic regularity - estimates put the figure at once every decade, though not all of these have been directly observed. The last Supernova event, a type Ia, in M82 was observed in January 2014 and brightened to +8 mag - it was the closest and brightest observed Supernova since the LMC Supernova in 1987.

In addition to M81 and M82, a smaller outlying galaxy, NGC 3077, which is a 5.2 x 4.7 arc minute +9.89 mag object, forms a sort of equilateral triangle with its two more dominant neighbours. This is a little more difficult from a visual perspective, though shows up well in images.

You don't need a large telescope to observe these galaxies, binoculars and a reasonable sky will show them, but the beauty of M81 and the mysterious nature of M82 are a joy to behold in a medium to large-sized telescope.

The curious Coddington's Nebula, IC 2574, lies around 3 degrees to the E of M81 and M82 in the direction of Dubhe, Alpha Ursae Majoris. This galaxy is an outlying member of the M81 group too. At +10.39 mag and 13.2 x 5.4 arc minutes area, it is somewhat low in surface brightness and not nearly as conspicuous as its neighbours - subsequently it was overlooked until Edwin Foster Coddington discovered it in 1898.

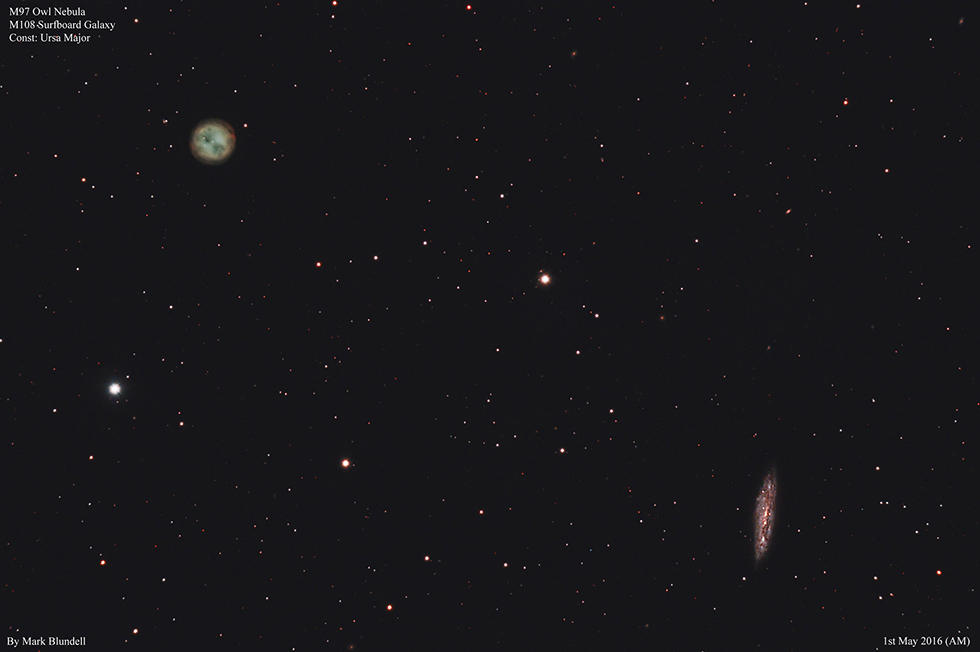

Follow Duhbe down the "Bowl" of the Big Dipper to Merak, or Beta Ursae Majoris. A degree and a half E of Merak lies another "odd couple" - the galaxy M108 and the planetary nebula, M97, otherwise known as the Owl Nebula. Both were discovered by Pierre Mechain in the early 1780s, though M108 was not officially added to the Messier list until the 1950s. M108 is a fine spiral galaxy, viewed nearly edge on and showing a distinct mottling in its texture. At +10 mag and 8.6 x 2.4 arc minutes, M108 can be seen fairly easily in most small telescopes and shows some notable H II nebulous regions with a UHC filter or similar in larger scopes. This galaxy is thought to be an outlying member of the M81 group and lies some 35 million light years away.

M97, or the Owl, is much closer at 1900 light years away and is very much a part of our galactic neighbourhood - its association with its neighbour is merely a lucky line of sight event and has no further significance than that. Unlike M108, the Owl was originally classified by Messier in 1781. When one observes the Owl through a reasonable sized telescope, most successfully when using an OIII filter, the reason for its nickname become apparent. This Planetary shows two distinct dark "eyes" like the face of an owl looking out through the cosmic gloom. These eyes are simply regions in the toroidal structure of the nebula where there are voids of gas - these are quite common features of many Planetary nebulae - the less material in these sections leads to a lower contrast area. The Owl has a central star, which is difficult to observe in smaller telescopes.

This pair of lovely objects, much like M81 and M82 is understandably a perennial subject for imagers.

Moving East along the bowl of the Dipper, or the blade of the Plough, we come to Phecda, or Gamma Ursae Majoris. Some 38 arc minutes to the E of Phecda is the stunning galaxy M109. Like M108, this is a latter addition to the Messier list, though discovered by Mechain in 1781. M109 is a +9.80 mag, 7.5 x 4.4 arc second target and one of the most beautiful Barred Spiral Galaxies in the entire sky. It can be spotted in binoculars under good conditions, though larger telescopes are needed to show evidence of its spiral arms and prominent central bar. M109 has three major arms which become evident under higher magnification in larger telescopes, though suffered the indignity of being incorrectly classified as a Planetary nebula by Sir William Herschel. Under lower magnification, M109 looks distinctly egg-shaped, so this might go some way to explaining the great Astronomer's error! Lying around 75 million light years away, M109 is the most prominent member of the larger Ursa Major group of galaxies, which are distinct from the closer M81 group.

From M109, we now travel up the bowl of the Big Dipper, along the handle, passing Megrez, Alioth and the double star Mizar and Alcor. If we continue to trace a line from Alioth, through Mizar, to the point where this line would be bisected by a perpendicular line moving up Northward from the last star in the handle, Alkiad, we come to the location of the last of the galaxies in Ursa Major we will cover this month: the face-on spiral M101.

M101 is a large galaxy, taking up an area 28.8 x 26.9 arc minutes across - much larger than even M81. Although its brightness is listed as around +7.9 mag, due to its face-on presentation, this brightness is spread over a very wide area, leading to quite a dim overall target. This galaxy was discovered by Mechain in 1781 and is one of the final original Messier objects, as it was added to the list by Messier later in the same year. Although studied by many astronomers in the interim period, it was only when Lord Rosse turned his 72-inch Leviathan of Parsonstown Reflector towards it in 1851 that its true spiral nature was revealed. Although some observers claim to have seen the first suggestion of spiral structure with instruments as small as 4 inches aperture, it will take exceptional sky conditions to be able to achieve this - or a much larger telescope. Larger telescopes, when combined with UHC, or similar Hydrogen-responsive filters, will start to reveal some of M101's remarkably rich HII regions, where star formation is rife. Indeed, M101 is somewhat of a monster in size, as it is estimated to be twice the diameter of our own Milky Way. It lies around 22 million light years away.

Somewhat confusingly, M101 is one of the three galaxies in the sky known by the nickname "The Pinwheel" - M33 in Triangulum and M99 in Coma Berenices also share this title.

Moving on from Ursa Major, we dive South into neighbouring Canes Venatici - the hunting dogs. Whereas Ursa Major is a large constellation with prominent stars, Canes Venatici is exactly the opposite - but what it lack is bright stars, it certainly makes up for in galaxies!

The first and best-known of all these is the remarkable M51 - the Whirlpool Galaxy. The Whirlpool is possibly the archetypal face-on spiral galaxy. Whereas M101 is large and relatively faint, M51 at +8.39 mag and 11.2 x 6.9 arc minutes area is more compact and brighter. This galaxy has two massive spiral arms, bound around one another. On the tip of the Northern arm, is a companion galaxy, NGC5195, which is in the process of heavy tidal interaction with M51.

M51 is a true Messier object - it was discovered by him in 1773, though Pierre Mechain discovered NGC5195 later in 1781. Lord Rosse made a famous sketch of M51 through is 72 inch reflector in 1845, which clearly showed M51's Spiral and its satellite - it is this sketch that gave rise to the nickname "Rosse's Question Mark" - for obvious reasons.

Although M51 can be found relatively easily in binoculars, a dark sky will be needed to active this. Small telescopes will show M51's core easily and the first suggestion of a halo surrounding this. However, once the 12-inch barrier is broken in terms of aperture, then M51, really begins to come into its own. This aperture and above will show the Whirlpool in all its glory - and notable features such as the bridge between M51 and NGC5195 and M51's numerous H II regions really begin to stand out. However, it is in long duration images that M51 really reveals all - and in this respect is a constant source of inspiration to astrophotographers.

M51 is thought to be of a similar size to both our galaxy and M31, the Andromeda Galaxy, and lies around 27 million light years away.

Just under 40 arc minutes to the S of M51 lies the elliptical galaxy NGC5173, otherwise known as the Southern Integral Sign. Although +12.19 mag in brightness, it is relatively compact at just 1 x 0.9 arc minutes dimensions and is thus quite evident in small telescopes, though rather disappointingly bland in relation to the many spirals that surround it.

Just under 6 degrees to the South of M51 lies the lovely M63, the Sunflower Galaxy. This is a truly beautiful object - a tightly packed spiral with a bright core and fainter outlying arms. It certainly does look distinctly flower-like in long duration images.

The Sunflower has the distinction of being the first discovery made by Pierre Mechain - Charles Messier's partner and major contributor to his list. At +8.6 mag and 12.6 x 7.2 arc minutes across, M63 makes for a relatively straightforward target in most small telescopes, though larger instruments will be needed to make out the spiral structure. This was first noted by Lord Rosse during his survey of spiral nebulae during the 1840s.

M63 is thought to lie around 34 million light years from us and is part of the group of galaxies in this area of sky of which M51 is the dominant gravitational member.

4 and 3/4 degrees to the W of M63, we find the distinct galaxy M94, which was another discovery of Mechain in 1781 - and was added to the Messier list in the same year. M94 is, like its major neighbours, a spiral galaxy - albeit a rather unusual one. At +8.19 mag and 14.1 x 12.1 arc minutes area, M94 lies about half the distance from us - 14 million light years - than either M51 and M63. Its structure is notable - a tight compact, very bright spiral core, surrounded by two concentric fainter rings of stars. It is due to this structure that it has gained the nickname in some circles of the Cat's Eye Galaxy. This suggestion of spiral structure shows up well in even small telescopes, though instruments of 8-inches aperture + are needed in order to see much of the outer rings. M94 can be found in binoculars, if sky conditions are kind though a telescope is definitely needed to see anything more than a faint smudge. When imaged, M94 gives up considerable detail, especially in its outer ring.

Just over 5 1/2 degrees further S from M94, lies NGC5005 - yet another spiral galaxy. At +9.80 mag and 5.8 x 2.9 arc seconds area, this object has a really bright nucleus, surrounded by a much darker, almost sooty-looking outer arms. In larger telescopes, the elongated aspect of NGC5005 really begins to revel itself, though in truth, this galaxy is a rather disappointing object in smaller instruments and binoculars.

Under 7 1/2 degrees to the SW of NGC5005, sits the slightly easier to observe NGC4631, otherwise known as the Whale Galaxy. This +9.19 edge-on spiral galaxy does indeed resemble a galactic whale swimming through the cosmos. At 15.2 arc minutes long by just 2.8 arc minutes wide, the Whale has quite high surface brightness and is therefore a relatively easy object in most large binoculars and small telescopes. A companion galaxy, NGC4657, sits to the N of the Whale and is thought to be responsible for some of the larger galaxy's elongation. Both objects lie around 25 million light years away and were discovered by Sir William Herschel in 1787. To the SE of the Whale, by around half a degree, sits another spiral galaxy, NGC4656, otherwise known as the Hockey Stick. Photographic evidence reveals why, as one edge of NGC4656 appears bent - just like a hockey stick. Just like NGC4631, the Hockey Stick was discovered by Herschel, though lies a little further from us than its neighbour, at 30 million light years away..

Under 8 degrees to the NW of the Whale, lies the superficially very similar NGC4244 - the Silver Needle Galaxy. This is another spiral which lies edge-on to our perspective and although a little fainter at +10.6 mag than its neighbour is well worth seeking out. At 16.6 x 1.9 arc minutes in area, the Silver Needle has a somewhat lower surface brightness that the Whale, but is impressive enough in larger telescopes. Although difficult to see from our point of view, NGC4244 is thought to be a barred spiral structure with two wide arms. Sources differ as to the distance this galaxy lies from us, with most seeming to favour the 14 million light years mark, though some putting it as close as 6.5 million light years away. If the latter is closer to the truth, NGC4244 is possibly an outer member of our own local group rather than a galaxy belonging to the Canes Venatici family.

4 1/2 degrees to the NE of NGC4244 sits two interaction galaxies, NGCs 4485 and 4490 - otherwise known as the Cocoon. These 6.4 x 3.2 arc minute objects have a cumulative magnitude of +9.80 and have undergone a catastrophic interaction with each other - much as the Milky Way and M31 are thought to experience in the far future. Although both galaxies are now moving away from each other, there are some remnants of spiral structure left in a massive arc of stars and material stretching 24000 light years in length between both objects. This seemingly destructive interaction, as it often does, has sparked a huge amount of star formation in this region. Both galaxies - or what's left of them - are thought to lie some 31-50 million light years away from us.

2 1/2 degrees to the N of the Cocoon, sits NGC4449. This galaxy is something of a rarity in this part of the sky, being of an irregular, rather than a spiral structure.

NGC4449 was discovered by Sir William Herschel in 1788 and is +9.6 mag in brightness and 6.4 x 4.4 arc minutes in size. NGC4449 is superficially very similar to the larger of our two satellite galaxies, the Large Magellanic Cloud, though observations of this diminutive galaxies in radio wavelengths have revealed that the visible part of NGC4449 is dwarfed by a huge, optically invisible halo of gas, which is 14 times its diameter. NGC4449 is easily enough found in larger telescopes, and the mottling of its HII regions is impressive if enough aperture is directed its way - though admittedly this galaxy does lack some of the glamour of its neighbours.

Just over 3 1/2 degree to the N of NGC4449, lies the last galaxy in our epic jaunt around this area of sky - M106. This +8.39 mag spiral galaxy was discovered by Mechain in 1781, but was not added to the catalogue by Messier at the time. M106 is, like some previously mentioned galaxies, a later, 20th century addition to the original list. M106 is a fine galaxy - well presented from our perspective and bright enough to be seen in diminutive telescopes. However, a 12-inch + class of telescope will really start to reveal the two massive bound spiral structure of the arms and the darker material that lies between. At 18.6 x 7.2 arc minutes, M106 is a healthy size for a galaxy - larger than M51 and as such, should probably get a little more attention than often does.

Original text - Kerin Smith

English

English